Blocked ports are a common obstacle in web scraping, automation, and other high-volume online workflows, often appearing without clear explanations. While these blocks can seem arbitrary, they’re usually triggered by specific traffic patterns or infrastructure limitations. In this article, we’ll explain the most common reasons ports get blocked, how factors like concurrency, port reuse, and proxy network type influence blocking, and what practical steps you can take to reduce port-level restrictions at scale.

The Most Common Reasons Ports Get Blocked

In most cases, it’s the result of automated security systems reacting to traffic patterns that fall outside what’s considered “normal” behavior:

High Request Concurrency on a Single Port

One of the most frequent causes is sending too many simultaneous requests through the same port. From the target server’s perspective, dozens or hundreds of parallel connections originating from one IP/port pair can resemble bot activity or abuse, even if the requests themselves are legitimate.

Many modern systems monitor connection density per port and may temporarily throttle or fully block ports that exceed expected usage levels.

Unusual or Repetitive Traffic Patterns

Even at moderate volumes, highly repetitive behavior can raise flags. This includes:

- Identical request intervals

- Repeated access to the same endpoints

- Long-running sessions with no natural pauses

When these patterns are consistently tied to a specific port, that port may be restricted independently of the IP address.

Shared Infrastructure and Inherited Reputation

On shared networks, ports don’t exist in isolation. If multiple users operate through the same infrastructure, a port may inherit a negative reputation due to earlier abusive or non-compliant traffic.

In these cases, blocks can occur even if your own usage follows best practices, simply because the port has already been flagged by the target platform.

Rate Limiting and Abuse Prevention Mechanisms

Some platforms don’t immediately block IP addresses. Instead, they apply controls at the port or connection level:

- Limiting the number of open connections per port

- Dropping requests once a threshold is reached

- Temporarily refusing new connections

What starts as rate limiting can escalate into a full port block if the behavior continues.

Network Type Restrictions

Certain websites apply stricter rules depending on where the traffic comes from. Ports associated with specific network types – such as datacenter environments – may be monitored more aggressively than those typically used by end users.

In these cases, the port itself isn’t the core issue, but rather the network behind it and how that network is commonly used.

Local or Upstream Network Policies

Not all port blocks originate from the target website. Firewalls, corporate networks, hosting providers, or ISPs may restrict outbound or inbound traffic on specific port ranges, especially if they detect high-volume or automated usage.

These restrictions are often mistaken for target-side blocking but require a different troubleshooting approach.

High Concurrency and Port Reuse

High request concurrency is one of the fastest ways to trigger port-level restrictions. While parallel requests are often necessary for efficient data collection, how those requests are distributed across ports and IP addresses makes a significant difference.

Why Concurrent Requests Get Flagged

From a target server’s point of view, a large number of simultaneous connections arriving through the same port looks abnormal. Even if the requests are valid, this pattern closely resembles automated scraping or brute-force behavior. As a result, many platforms enforce limits on how many parallel connections a single port can sustain.

Once these thresholds are exceeded, the server may begin throttling requests or blocking the port entirely.

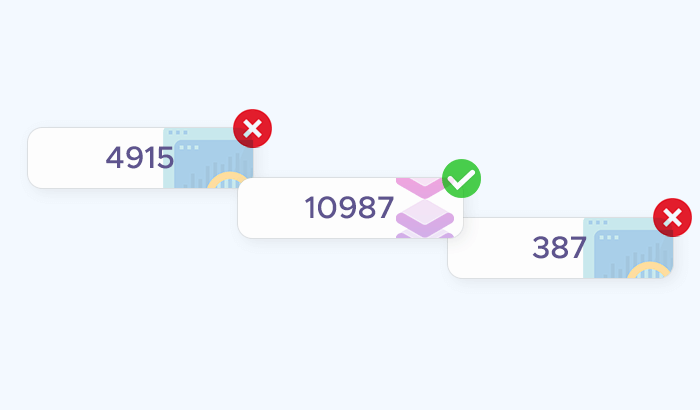

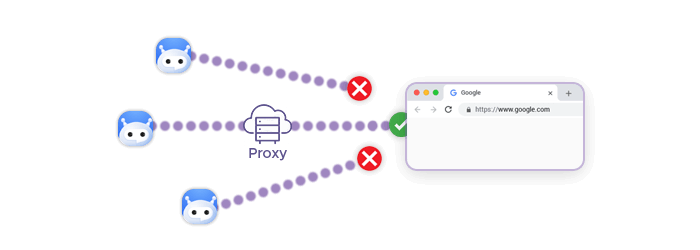

Port Reuse vs. Port Distribution

Reusing a single port for multiple concurrent tasks concentrates all activity into one connection point. This creates a clear signal for detection systems, especially when requests are sent at high speed.

A more resilient approach is to distribute concurrent requests across multiple ports. When each task uses its own port, traffic appears more balanced and closer to typical user behavior, reducing the likelihood of port-level restrictions.

One Port, One IP Address

In many proxy infrastructures, each port is mapped to a unique exit IP address. For example, connecting through the same hostname with different ports results in separate IPs behind the scenes.

This means that spreading requests across ports doesn’t just reduce port pressure – it also naturally distributes traffic across multiple IP addresses, further lowering detection risk.

Scaling Concurrency Safely

For larger workloads, effective concurrency management requires access to a sufficiently wide port range. Being able to operate hundreds of ports in parallel allows you to scale horizontally instead of pushing excessive load through a single connection. This approach helps:

- Maintain stable connection success rates

- Avoid sudden port blocks during traffic spikes

- Keep long-running scraping jobs operational

Rather than increasing request speed on one port, scaling across many ports is typically safer and more sustainable.

How Proxy Network Type Affects Port Blocking

| Proxy Type | Port Behavior | Concurrency Tolerance | Session Stability | Typical Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residential | Ports generally experience fewer blocks due to real-user traffic patterns | Moderate to high | Medium; IPs can rotate occasionally | Sensitive websites, geo-specific access, targets with strict bot detection |

| Static ISP | Ports are stable and tied to long-lived IPs, reducing unexpected blocks | High | High; stable IPs and ports | Long-running sessions, account-based workflows, moderate to strict targets |

| Mobile | Ports tolerate high request volumes and frequent IP changes | High | Medium; natural IP churn | Platforms with strict detection, session-sensitive tasks, rotating traffic patterns |

| Residential IPv6 | Vast address space reduces pressure on individual ports, lowering block risk | High | High; traffic can be spread across many IPs | Large-scale scraping, IPv6-enabled platforms, high concurrency workloads |

How to Reduce Port Blocking in Practice

While port blocking can’t be eliminated entirely, it can be significantly reduced with the right setup and usage patterns. In most cases, small configuration changes are enough to turn unstable connections into reliable, long-running workflows.

Distribute Concurrent Requests Across Ports

Avoid sending multiple simultaneous requests through the same port. Instead, assign separate ports to parallel tasks so traffic is spread evenly. This reduces connection density per port and makes activity appear more natural to target systems.

Horizontal scaling across many ports is generally safer than pushing high throughput through a single connection.

Take Advantage of One-Port–One-IP Mapping

When each port corresponds to a unique exit IP, spreading traffic across ports also distributes requests across IP addresses. This lowers the risk of both port- and IP-level blocks and helps prevent sudden drops in success rates during traffic spikes.

Planning concurrency around port/IP pairs makes scaling more predictable.

Match Proxy Type to Target Sensitivity

Not all targets apply the same detection rules. For stricter platforms, residential, mobile, or static ISP networks tend to tolerate more activity before blocking ports. Less sensitive targets may work well with datacenter proxies, especially when ports are dedicated.

Choosing the right network upfront often reduces the need for aggressive retries or complex workarounds.

Avoid Excessive Port Reuse

Even with moderate traffic, repeatedly reusing the same ports across different jobs can build up a negative reputation over time. Rotating ports between tasks or assigning dedicated port ranges per project helps isolate risk and keeps issues from spreading.

Monitor Early Warning Signs

Port blocking rarely happens without warning. Increased latency, connection drops, or frequent rate-limit responses often indicate that a port is under pressure. Responding early – by reducing concurrency or switching ports – can prevent a full block.

Keep Local and Upstream Restrictions in Mind

If ports fail consistently across different targets, the issue may be local. Firewalls, hosting providers, or corporate networks can restrict certain port ranges. Verifying that outbound connections are allowed can save hours of unnecessary troubleshooting.

A Simpler Way to Manage Ports at Scale

With structured port ranges, predictable port-to-IP mapping, and multiple proxy network options, Infatica’s proxy infrastructure makes it easier to distribute load, isolate risk, and keep connections stable as demand grows.